Once a personal and communal craft rooted in rural life, tatreez has transformed into a global symbol of Palestinian identity, resilience, and resistance.

Text by Rachel Dedman

Tatreez is the Arabic word for the elaborate hand-embroidery used in Palestinian dress. It is one of Palestine’s most significant cultural traditions, renowned for its beauty and complexity. Each region is known for distinct embroidery techniques, stitches and motifs, which contribute to the remarkable diversity of tatreez. In its heyday in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tatreez was a language as much as a craft. The clothing a woman made for herself reflected her identity, her character and her origins, as well as the changing nature of her life. Written into garments are the signs of youth or grief, the marks of motherhood and rural life, as well as the traces of social, political and economic change in Palestine, which are present in the very fabric of her clothing. The wielding of needle and thread is primarily an individual practice, and embroidery was traditionally done for a woman’s own use. But tatreez has always been embedded in community and involved in shaping collective identity in ways that have changed significantly over the last hundred years. Looking closely at clothing allows us to trace an intimate, human history of Palestine, following the evolution of embroidery from a personal practice rooted in village life into a symbol of nationhood, a tool of resistance and a practice of solidarity in the present.

Embroidery’s historic community ties

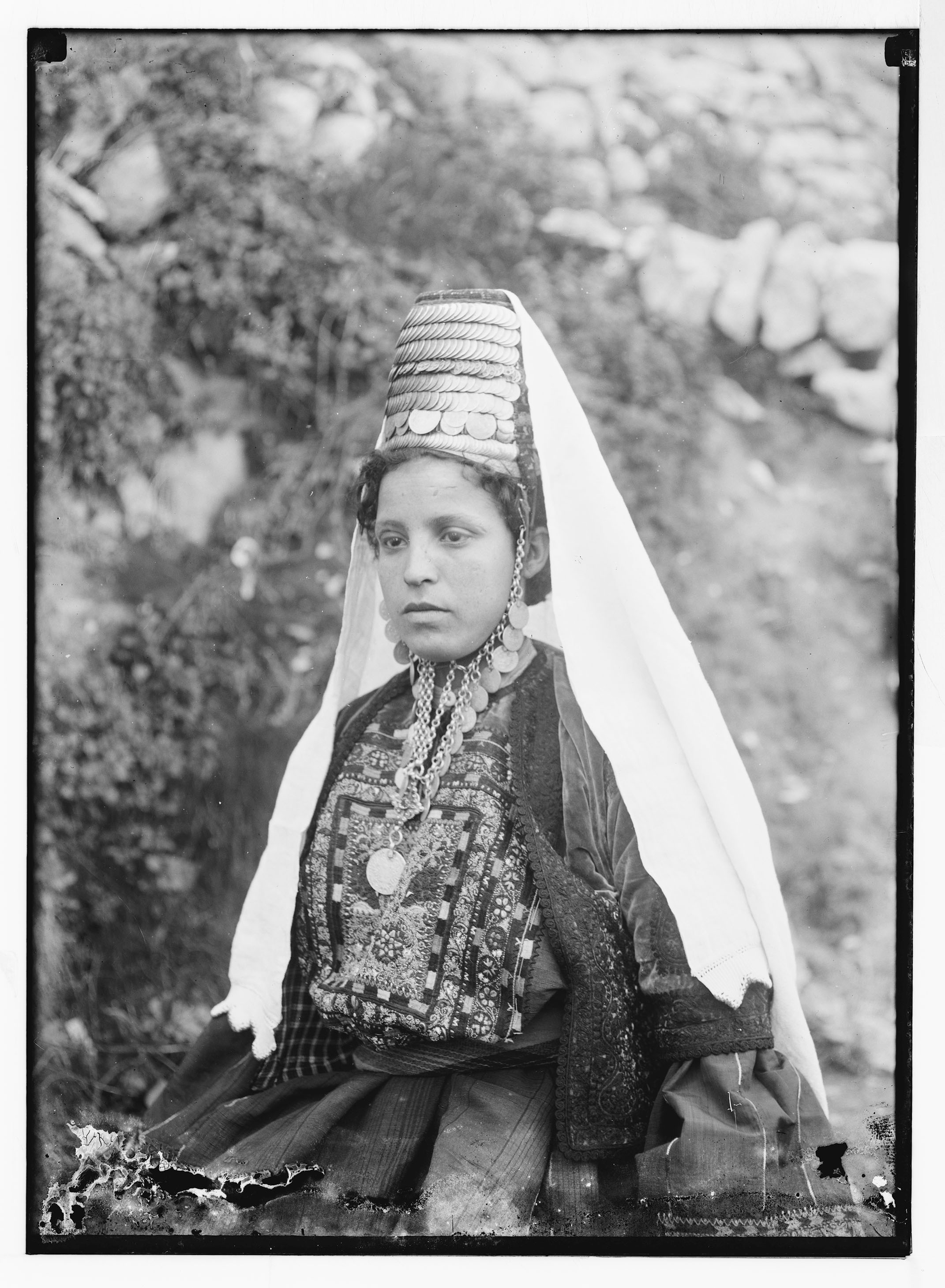

Tatreez was historically the craft of fellahi (peasant) women. Until 1948, girls were taught to stitch by their mothers or grandmothers at the age of six or seven, and would begin to embroider a trousseau of clothing to take with them into marriage. Palestinian embroidered dress is best known in its most spectacular form — wedding and special occasion dresses women created for life’s most important rites of passage.

Before and after marriage, embroidery was integrated into women’s working lives in agriculture and the home. Garments were stitched in sections, which made embroidery conveniently portable. Women would sit together by the well to embroider, or in the courtyards of their homes, pausing during the day to stitch and talk. Young women and girls grew up learning about tatreez by watching their network of female family, friends and neighbours stitch together. They absorbed the meaning of the motifs associated with their village dress and practised the techniques particular to it. It is in these communal female settings that the knowledge of tatreez was handed down, along with other craft as an oral tradition as much as a physical one. Palestinian fashion in this period was remarkably diverse, and women could ‘read’ or interpret the embroidery on other women’s clothing, recognizing where they were from.

Morocco–Spain, 2001, Bulgaria–Turkey, 2014, Mexico-United States, 2017, Israel-Gaza, 1994

Bethlehem is famous for an embroidery technique called couching (tahriri), where silver or gold-wrapped cord is coiled on fabric in swirling patterns. Taqsireh jackets of velvet or felt were worn over striped dresses with long fluted sleeves. Particularly during the British Mandate period (1918–1948), patterned cottons woven in Britain were imported into Palestine. Women often lined their jackets with these fabrics as a mark of wealth and status.

Suleiman Mansour, postcard, 1980s, Omar al-Qasim Collection, the Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

As well as asserting local pride, tatreez held family history. Palestinian women cherished their dresses and handed them down to the next generation, who would rework garments inherited from their mothers and grandmothers. Embroidery is a practice that reinforces fabric, so if a dress was well-worn, it was usually the non-embroidered parts that frayed. Women would discard these and graft the remaining embroidered sections onto a fresh base or existing dress. Garments which hold the traces of several embroiderers work challenge the impulse of curators or art historians to treat them as definitive museum objects, with a singular maker and clear date of creation. In Palestine, dresses are more like mosaics, shaped and shared by many hands over time.

Community in times of crisis

The events of 1948, known as the Nakba, or catastrophe, changed the lives of everyone in Palestine. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were forcibly displaced from their homes by Zionist forces and became refugees in makeshift camps within the West Bank, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria. Thousands were killed in the battle to resist dispossession and ethnic cleansing.

Dress from Ramallah, 1930s with later additions, from the collection of Maha Abu Shosheh. Photo Kayane Antreassian. Courtesy the Palestinian Museum

A dress in the collection of Maha Abu Shosheh — a Ramallah-based private collector of tatreez who is dedicated to preserving Palestinian heritage — embodies the human impact of the Nakba. We can tell by its style that it was made by a woman from Ramallah in the 1930s. In 1948, she donated it to another woman, who had been displaced from her home and walked into the West Bank carrying perhaps nothing else to wear but the clothing she had on. It is evident that the woman who inherited the dress was taller and broader than the original embroiderer, as the garment has been enlarged with panels at the sides and around the waist. The makeshift material for this is sacking from a bag of flour, of the kind given out to refugees after the crisis by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency. The Arabic letter nuun (n), from the word tahin (flour), is faintly visible, stamped on the side in UN blue. The very materiality of the dress speaks not only to the urgency of the situation, but also to the generosity and resilience of women at what must have been one of the most difficult moments of their lives. It attests to the way something as simple as clothing can embody community in moments of crisis.

Embroidery as national identity

The Nakba dramatically altered embroidery’s connection to daily rural life. Living in refugee camps, most women could no longer afford to embroider as they once had, and the cottage industries and haberdashers that had supported the craft were gone. Embroidery persisted, however, evolving into a practice of paid work, but tatreez also began to take on symbolic meaning that transcended the body.

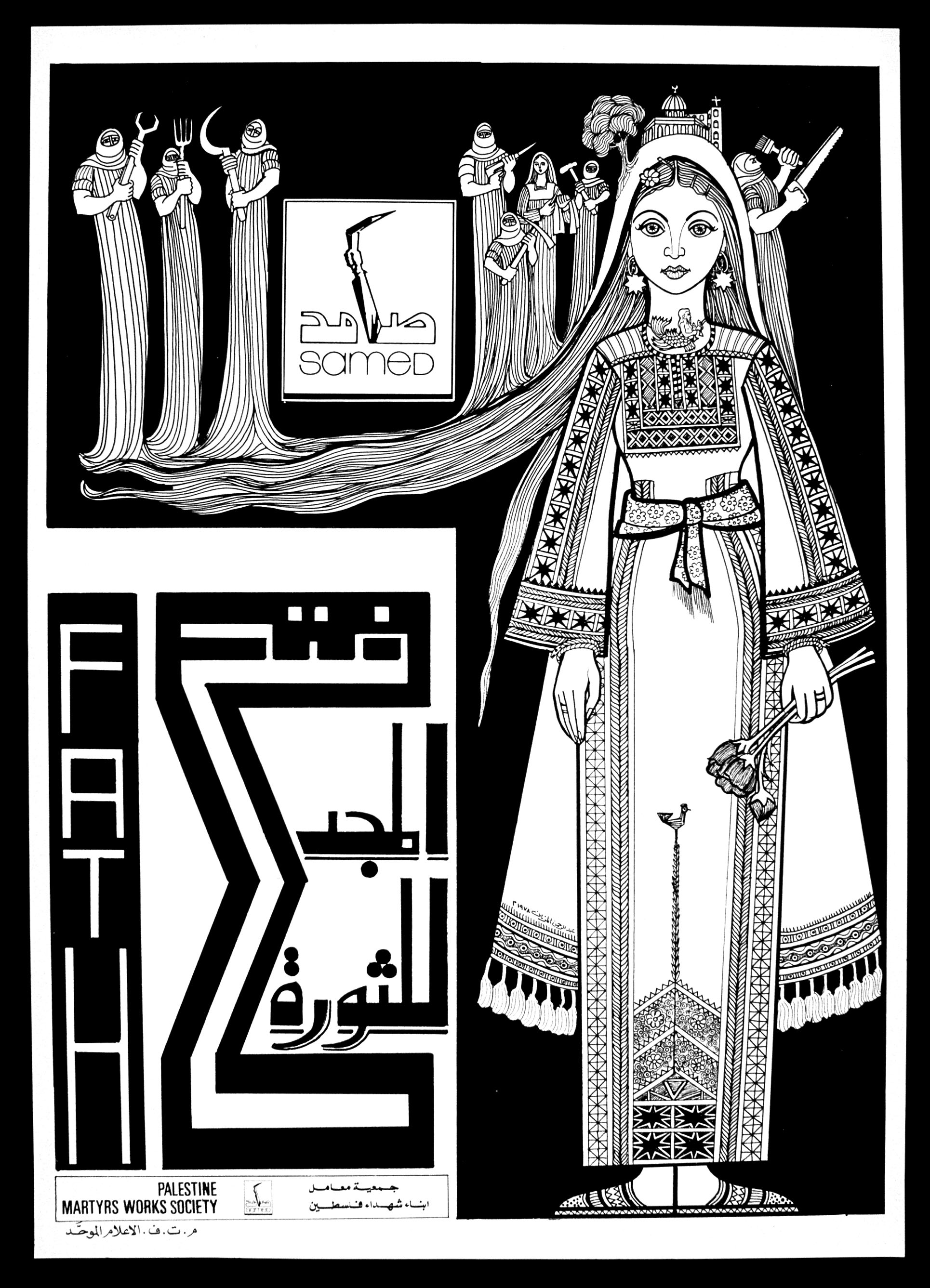

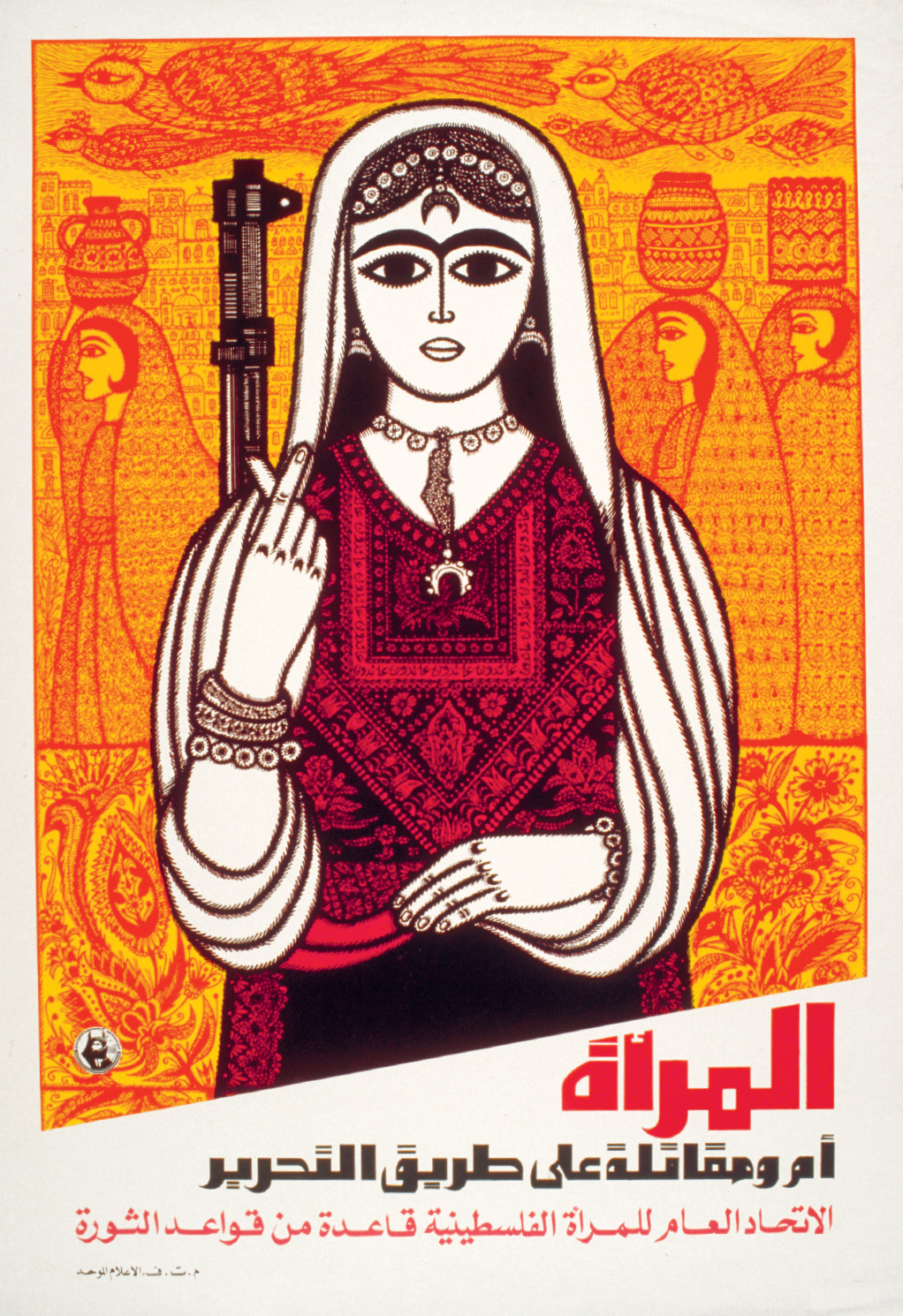

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Palestinian Liberation Organisation championed a revival of traditional heritage, prompted in part by Israel’s appropriation of Palestinian culture. In this process, tatreez emerged as a key symbol of Palestinian identity. Through its association with the rural fellahi woman and her deep connection to the land, the ancient craft of tatreez served as evidence of the historic presence of Palestinians in Palestine. The figure of the ‘embroidered woman’ became a prominent symbol in the work of Palestinian Liberation Artists such as Sliman Mansour, Nabil Anani and Abdel Rahman Al-Muzayyen. By the 1980s, the motif of the rural Palestinian woman — always represented wearing an embroidered thobe — was well-known and widespread, circulating on posters within Palestine and internationally as part of growing solidarity movements.

The representation of tatreez by artists and in Palestinian material culture signalled a significant shift in value. Before the Nakba, rural women had little cultural or political visibility in Palestine. The political class had long been dominated by an urban Palestinian elite, who had worn European or Ottoman dress for centuries. The Nakba and the struggle for Palestinian liberation politicized tatreez, transforming it from a peasant craft with complex, personal meaning for those who practice it, into a simplified, yet widely recognized signifier of national identity.

1. Lorenzo Lotto, Family Portrait, 1524. Courtesy Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Burhan Karkoutly, Mother and Fighter, published by the General Union for Palestinian Women, c. 1978. Images the Palestine Poster Project Archive

The First Intifada

The politicization of tatreez reached its peak during the First Intifada — a mass popular uprising against the Israeli military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza — which began in 1987. As young men were arrested or shot at protests, women took on a more visible role on the front lines of the struggle. At this time it was illegal to display Palestinian colours in public or fly the Palestinian flag, so women began stitching explicit symbols of resistance onto their clothing, creating what came to be known as ‘Intifada dresses’.

Installation view of Material Power: Palestinian Embroidery at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge.

Photo Jo Underhill

Photo Jo Underhill

Intifada dresses combine traditional motifs embroidered in Palestinian colours with a new symbolic vocabulary. On one dress, doves soar across the chest, flanked by rifles, love hearts and crossed swords. Holy sites like the Dome of the Rock or Al-Aqsa Mosque appear on others. The map of Palestine is repeated as a pattern, alongside expressions of political allegiance, such as the letters ‘PLO’.

PLO Bulletin, vol 4, no. 1, January 1978. Courtesy the Institute of Palestine Studies, Beirut

These Intifada Dresses turned women’s bodies into sites of active political agency in protest. The garments reinforced the collective power of those resisting occupation, drawing strength from an historical tradition of struggle for freedom in the present. What is also extraordinary about Intifada dresses is that they are not what we typically associate with the material culture of protest. Demonstrations often involve objects made relatively quickly — posters or banners printed, scrawled or painted in haste. But as anyone who has ever embroidered anything will know, tatreez is the opposite of spontaneous. These dresses are the product of long, painstaking effort — stitched in secret, often without electricity, in villages under siege.

The extended temporality of embroidery as a practice embodies the notion of sumud, or steadfastness, and reflects the idea that resistance is a process, not an event. As Subhiye Krayem, an embroiderer in Ein el-Hilweh camp in Lebanon, once put it to me in an interview: “Folklore is a politics unto itself. It means that I exist.”

Tatreez Today

Since October 2023, the world has paid greater attention than perhaps ever before to the plight of Palestinians and has witnessed genocide in Gaza. In this context, tatreez has once again taken on new meaning. All over the globe, people have taken up the craft for the first time — both Palestinians in the diaspora seeking to connect with their heritage, and those standing in solidarity with Palestine. Social media has enabled young audiences to begin practicing tatreez themselves. Stitching circles dedicated to the craft — both in real life and online — have proliferated, while embroidery kits, online tutorials and web resources are now widely available.

This is one legacy of the politicization tatreez since 1948, and a new expression of the craft as a form of resistance. When watching horror unfold from afar, there is something meaningful, connective and cathartic in engaging with a tradition from that place. In paying respect to the craft by learning it, and in so doing, shrinking the distance between yourself and generations of Palestinian women. There is something quietly powerful about a tatreez circle, in which the act of communing with others is often more important than the stitching itself. While women a century ago embroidered together around their village well, people today connect over TikTok or Instagram, forging a global community of embroiderers. From the village to the virtual, in Palestine and beyond, tatreez persists as a craft of the collective.